"Androcide"

Excerpts from the unpublished manuscript (in review) titled, “Androcide – Professional Wrestling as a Death Cult” (195 pages)

Wrestling Gimmick: Ted DiBiase's Money and Million Dollar Belt

"The Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase was a coveted heel for the glorious “Hero” era of professional wrestling. Through his obnoxious demeanor and opulent presentation, DiBiase never missed an opportunity to make the little people of the crowd feel like worthless bugs. However, DiBiase was equally apt at humiliating his opponents in the ring not only through a debilitating finisher (a sleeper hold) but also by crumpling up dollar bills and leaving them in the gaping maw of his fallen, unconscious foes. Although officially an unsanctioned championship, The Million Dollar Belt, became a powerful gimmick for catalyzing fresh rivalries for the WWF during the early 1990s. His self-proclaimed financial endowments brought legitimacy to that championship while DiBiase became an x-factor in the kayfabe representation of power hierarchy for the WWF promotion (DiBiase reiterated this effect as “Billionaire Ted” for the nascent nWo faction of the WCW, several years later).

"The Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase was a coveted heel for the glorious “Hero” era of professional wrestling. Through his obnoxious demeanor and opulent presentation, DiBiase never missed an opportunity to make the little people of the crowd feel like worthless bugs. However, DiBiase was equally apt at humiliating his opponents in the ring not only through a debilitating finisher (a sleeper hold) but also by crumpling up dollar bills and leaving them in the gaping maw of his fallen, unconscious foes. Although officially an unsanctioned championship, The Million Dollar Belt, became a powerful gimmick for catalyzing fresh rivalries for the WWF during the early 1990s. His self-proclaimed financial endowments brought legitimacy to that championship while DiBiase became an x-factor in the kayfabe representation of power hierarchy for the WWF promotion (DiBiase reiterated this effect as “Billionaire Ted” for the nascent nWo faction of the WCW, several years later).

The Birth of the Wrestling Anti-Hero: WCW Monday Nitro, May 27th, 1996

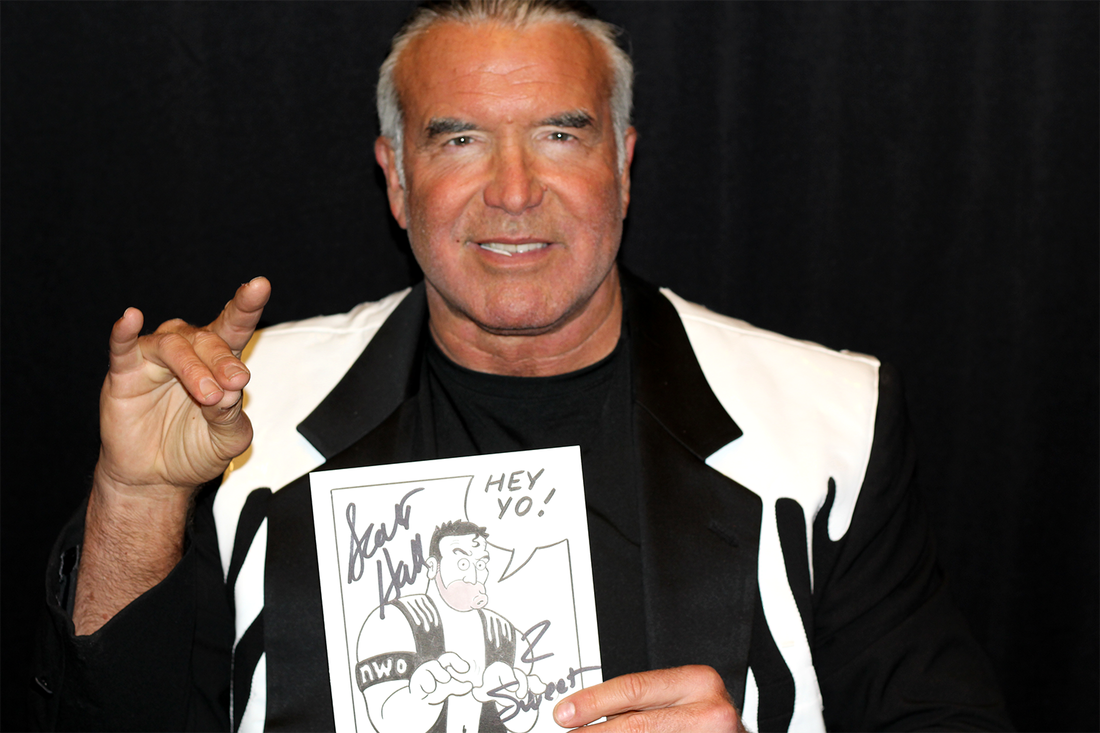

When Scott Hall appeared in front of the cameras on the May 27th episode of WCW Nitro, he did so through emerging from among the crowd, hopping the guard rail, stripping the mic from the stopwatch referee sitting ringside, and then entering the ring during a jobber match with his expressed purpose of announcing the start of the “hostile takeover” of WCW by the nascent nWo bully faction. It was as if a light went on for fans everywhere as they could finally make sense of the deluge of talent that had flooded into WCW from the WWF during the previous year.

Appropriately, Hall’s proclamation came during the first two-hour episode of Monday Nitro, and the spectacular show would soon present a weekly card with depth akin to a pay-per-view event. The WCW stable of stars would increase steadily for more than a year. That Monday night, Hall stood confidently in the center of the ring chuffed by his role as herald for the new Anti-Hero era of professional wrestling, and although he quickly shed his bad Cuban accent that had been developed for his WWF Razor Ramon shtick, his popular “Bad Guy” heel persona remained largely intact. The suspense of teasing-out the formation of the nWo was immaculate in its execution, and the industry was now a big business relying on talented Hollywood producers and writers, thus replacing the amateur storytelling and organization of the previous era of managers and booking agents.

Scott Hall transgressed the very space of the arena by entering from the crowd. This sense of impromptu invasion became a theme for the nWo bully faction and many of their early segments featured the megastar wrestlers occupying the previously repressed spaces of the show, such as, the locker rooms, hotel rooms, back lots, parking lots, and of course the spectator stands at the venues each week. The nWo appeared among the crowd on several occasions, thus flattening the hierarchy of attention and focus for spectators in the stadium as well as for audiences watching at home. Suddenly, the spectators were a sidekick in the show itself. It is no wonder that nWo signs and t-shirts began to proliferate among the fans at breakneck speed. The crowds quickly became an undulating sea of fan-based branding in recognition of allegiance to their wrestling icons – hero and anti-hero, alike.

When Scott Hall appeared in front of the cameras on the May 27th episode of WCW Nitro, he did so through emerging from among the crowd, hopping the guard rail, stripping the mic from the stopwatch referee sitting ringside, and then entering the ring during a jobber match with his expressed purpose of announcing the start of the “hostile takeover” of WCW by the nascent nWo bully faction. It was as if a light went on for fans everywhere as they could finally make sense of the deluge of talent that had flooded into WCW from the WWF during the previous year.

Appropriately, Hall’s proclamation came during the first two-hour episode of Monday Nitro, and the spectacular show would soon present a weekly card with depth akin to a pay-per-view event. The WCW stable of stars would increase steadily for more than a year. That Monday night, Hall stood confidently in the center of the ring chuffed by his role as herald for the new Anti-Hero era of professional wrestling, and although he quickly shed his bad Cuban accent that had been developed for his WWF Razor Ramon shtick, his popular “Bad Guy” heel persona remained largely intact. The suspense of teasing-out the formation of the nWo was immaculate in its execution, and the industry was now a big business relying on talented Hollywood producers and writers, thus replacing the amateur storytelling and organization of the previous era of managers and booking agents.

Scott Hall transgressed the very space of the arena by entering from the crowd. This sense of impromptu invasion became a theme for the nWo bully faction and many of their early segments featured the megastar wrestlers occupying the previously repressed spaces of the show, such as, the locker rooms, hotel rooms, back lots, parking lots, and of course the spectator stands at the venues each week. The nWo appeared among the crowd on several occasions, thus flattening the hierarchy of attention and focus for spectators in the stadium as well as for audiences watching at home. Suddenly, the spectators were a sidekick in the show itself. It is no wonder that nWo signs and t-shirts began to proliferate among the fans at breakneck speed. The crowds quickly became an undulating sea of fan-based branding in recognition of allegiance to their wrestling icons – hero and anti-hero, alike.

Promoting Passive Audience Reception in Professional Wrestling

During the November 25th, 1996, episode of WCW Monday Nitro, the nWo bully faction "forcibly" expanded its roster through the wily machinations of Eric Bischoff, and in so doing Marcus "Buff" Bagwell became the next star of the nWo. A brawl ensued at the end of that show when the nWo raided the ring to beatdown both tag teams in the main event (Harlem Heat and Faces of Fear). The directing of the sequence was a visual feast from start to finish and its immaculate execution exemplified the production style of that era of professional wrestling.

Blocking is a critical element of directing in television and film production, which involves the director deciding where people or objects will be placed in the mise-en-scene in order to best bring the audience’s focus and attention to particular action and events. Blocking emphasizes a dynamic relationship within the network of objects in the scene whereby the viewer’s gaze is controlled at all time by the director. Directors utilize blocking techniques to make the audience see what the director wants them to see. Professional wrestling has a keen sense of blocking with respect to direction because there is constant action, yet the combat is simulated.

In televised ice hockey or football, the producer wants an unencumbered view of the big hit, however, in professional wrestling the big hit (or full impact of that hit) is simulated, therefore it is essential that the action be concealed creatively. In the 1980s and 90s, blocking was an art in the directing style for professional wrestling. Wrestlers had to sell moves effectively and the camera operators were placed in ideal positions around the ring to aid in that process. Drop-kicks often missed their mark and the wrestler being “hit” would throw up his hands to “sell” the move before falling back to the mat. If the camera operator had a straight-on angle for that drop-kick then the physical gap between the feet of the one wrestler and the face of the other would become blaringly obvious to a television audience, thus converting the viewer from a state of passive reception to a more active and critical reception, thus potentially encouraging disengagement with the entertainment aspect of the medium.

Arguably, to the chagrin of most “smarks” wrestling became a big business in entertainment production with the advent of television syndication. As such, there were important financial investors that demanded a certain level of technical sheen for the professional quality of the production. Extended rehearsals became the norm and wrestling matches were well-choreographed, much like a dance routine. Smarks have continued to affirm that moves are “called” virtually adlib during a match reflecting the creative whims of the performers, however, this style of production and performance is a relic of the past for professional wrestling. Of course, “calling” moves during a match in wrestling still happens much the same way that actors forget their lines when the cameras are rolling, and they must adlib through a scene. However, much like screen or stage actors, the wrestlers find opportunities to quickly step back into the rehearsed routine as soon as possible. Ergo, the wrestling directors and producers know the routines and have the camera operators arranged around the ring in order to capture action and block appropriately with the goal of helping the wrestler sell the moves and keep the audience engaged with the action at a passive level of viewership. The directors of wrestling yesteryear were magicians in this regard, demonstrating mastery in the art of 'sleight of punch' trompe-l’oeil, almost as if they assumed the role of a transcendental puppet master.

In recent years, WWE directing has become pervasively unindustrious in critical ways. The onus of selling moves is no longer on the wrestler but rather has shifted to the director and team of camera operators. The camera does all the selling now, whereby when a punch or kick is thrown, the camera zooms in quickly to create a visual blur for the action. The kinetic energy in the mobile framing and zoom effect emulates the imagined physical impact of the blow. WWE directors and producers proceed by picking a flattering angle for the action from among their network of camera operators and they quickly edit a replay sequence to be shown shortly after. However, the wrestling action becomes discombobulated and the events are perceived through their spatiotemporal dissonance. The effect of this directing style is to utilize repetition as a means of reinforcing control over the viewer and thus retaining them as a passive audience.

For the addicted fan of professional wrestling, the directing style being designed to compel passive viewership may be felt as desirable, however, I would like to suggest that the dilletante viewer finds the contemporary style of presentation intolerable. With the unindustrious directing and editing style, the wrestling moves lack a sense of serious impact, primarily because the viewer never sees a continuous sequence of action from start to finish. The experience is akin to reading a book, then having the book taken away just before the climax but then being given a summary of how the story ended in the words of another reader more familiar with the tale. I would conjecture that this unsatisfying style of authorship is partly responsible for professional wrestling losing its huge dilletante base of viewers that had been established during the height of Hulkamania in WWF and then during the rise of the nWo in WCW. In other words, professional wrestling currently lacks mass appeal, yet it could be argued that the current unindustrious directing style for professional wrestling has led to safer performances for the wrestlers and thus warded off the death cult aspect of the industry which dominated the medium in the 1980s and 90s.

During the November 25th, 1996, episode of WCW Monday Nitro, the nWo bully faction "forcibly" expanded its roster through the wily machinations of Eric Bischoff, and in so doing Marcus "Buff" Bagwell became the next star of the nWo. A brawl ensued at the end of that show when the nWo raided the ring to beatdown both tag teams in the main event (Harlem Heat and Faces of Fear). The directing of the sequence was a visual feast from start to finish and its immaculate execution exemplified the production style of that era of professional wrestling.

Blocking is a critical element of directing in television and film production, which involves the director deciding where people or objects will be placed in the mise-en-scene in order to best bring the audience’s focus and attention to particular action and events. Blocking emphasizes a dynamic relationship within the network of objects in the scene whereby the viewer’s gaze is controlled at all time by the director. Directors utilize blocking techniques to make the audience see what the director wants them to see. Professional wrestling has a keen sense of blocking with respect to direction because there is constant action, yet the combat is simulated.

In televised ice hockey or football, the producer wants an unencumbered view of the big hit, however, in professional wrestling the big hit (or full impact of that hit) is simulated, therefore it is essential that the action be concealed creatively. In the 1980s and 90s, blocking was an art in the directing style for professional wrestling. Wrestlers had to sell moves effectively and the camera operators were placed in ideal positions around the ring to aid in that process. Drop-kicks often missed their mark and the wrestler being “hit” would throw up his hands to “sell” the move before falling back to the mat. If the camera operator had a straight-on angle for that drop-kick then the physical gap between the feet of the one wrestler and the face of the other would become blaringly obvious to a television audience, thus converting the viewer from a state of passive reception to a more active and critical reception, thus potentially encouraging disengagement with the entertainment aspect of the medium.

Arguably, to the chagrin of most “smarks” wrestling became a big business in entertainment production with the advent of television syndication. As such, there were important financial investors that demanded a certain level of technical sheen for the professional quality of the production. Extended rehearsals became the norm and wrestling matches were well-choreographed, much like a dance routine. Smarks have continued to affirm that moves are “called” virtually adlib during a match reflecting the creative whims of the performers, however, this style of production and performance is a relic of the past for professional wrestling. Of course, “calling” moves during a match in wrestling still happens much the same way that actors forget their lines when the cameras are rolling, and they must adlib through a scene. However, much like screen or stage actors, the wrestlers find opportunities to quickly step back into the rehearsed routine as soon as possible. Ergo, the wrestling directors and producers know the routines and have the camera operators arranged around the ring in order to capture action and block appropriately with the goal of helping the wrestler sell the moves and keep the audience engaged with the action at a passive level of viewership. The directors of wrestling yesteryear were magicians in this regard, demonstrating mastery in the art of 'sleight of punch' trompe-l’oeil, almost as if they assumed the role of a transcendental puppet master.

In recent years, WWE directing has become pervasively unindustrious in critical ways. The onus of selling moves is no longer on the wrestler but rather has shifted to the director and team of camera operators. The camera does all the selling now, whereby when a punch or kick is thrown, the camera zooms in quickly to create a visual blur for the action. The kinetic energy in the mobile framing and zoom effect emulates the imagined physical impact of the blow. WWE directors and producers proceed by picking a flattering angle for the action from among their network of camera operators and they quickly edit a replay sequence to be shown shortly after. However, the wrestling action becomes discombobulated and the events are perceived through their spatiotemporal dissonance. The effect of this directing style is to utilize repetition as a means of reinforcing control over the viewer and thus retaining them as a passive audience.

For the addicted fan of professional wrestling, the directing style being designed to compel passive viewership may be felt as desirable, however, I would like to suggest that the dilletante viewer finds the contemporary style of presentation intolerable. With the unindustrious directing and editing style, the wrestling moves lack a sense of serious impact, primarily because the viewer never sees a continuous sequence of action from start to finish. The experience is akin to reading a book, then having the book taken away just before the climax but then being given a summary of how the story ended in the words of another reader more familiar with the tale. I would conjecture that this unsatisfying style of authorship is partly responsible for professional wrestling losing its huge dilletante base of viewers that had been established during the height of Hulkamania in WWF and then during the rise of the nWo in WCW. In other words, professional wrestling currently lacks mass appeal, yet it could be argued that the current unindustrious directing style for professional wrestling has led to safer performances for the wrestlers and thus warded off the death cult aspect of the industry which dominated the medium in the 1980s and 90s.

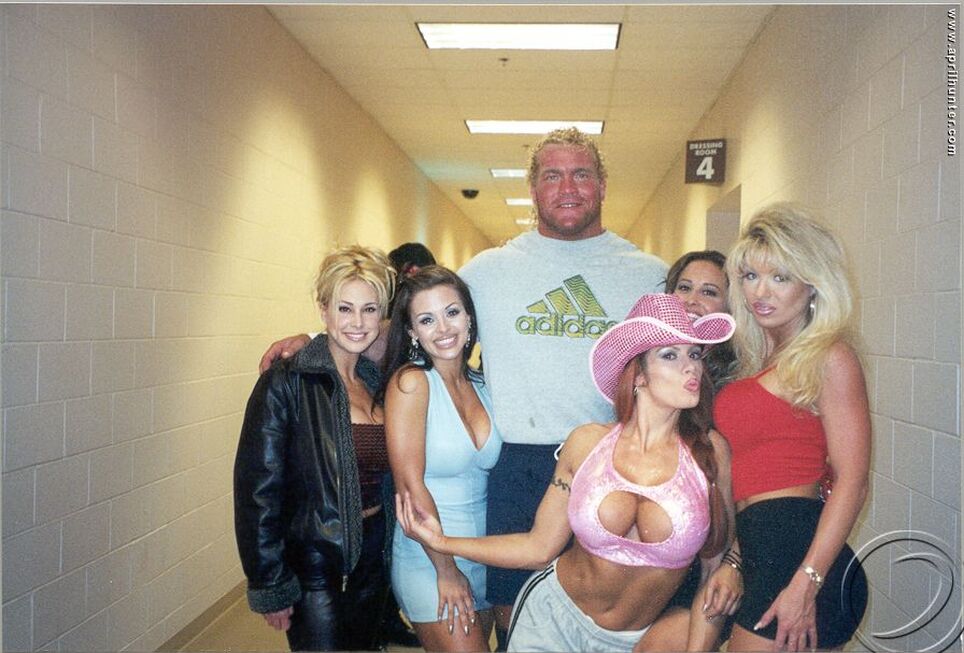

The Valet: The Way to Professional Wrestling’s Soul

The valet is a critical companion for the professional wrestler. She will often be seen at ringside cheering for her partner, but she can also serve as an effective distraction for the opponent and often for the referee. The valet is available for assistance during a match whereby she can pass illegal objects to her partner in the ring which often shifts the match back in their favour. Typically, the valet is demure, whereby she is seen but not heard. The valet is totally distinct from the diva (female wrestler) because the former will only become a combatant while under extreme duress. As such, the valet has been unduly criticized for being a damsel-in-distress stereotype.

WCW had an illustrious array of valets, especially during the Monday Nitro years. After 1999, professional wrestling put an undue emphasis on diva wrestlers, resulting in women in the industry being known more for their brutality than for their grace. I would conjecture that this has not been a positive complement to the male wrestlers and that it has chased away many of the dilettante viewers who in the 1980s and 90s had constituted the medium as having mass appeal. The feminine wiles of the valet once trumped the female savagery of the diva in professional wrestling, and this was a critical component for the cathartic release for male viewers. The valet representing the feminine became a psychological device for self-reflection for the male viewer whereby that male might use the valet’s character and representation to reflect on their own motivations for desiring base simulated violence and brutality.

The exemplar valet was Miss Elizabeth, and for professional wrestling she was magic. Her demure and coy personality was a perfect complement for the wild, madness of her long-time partner and real-life husband, “Macho Man” Randy Savage. Truly, they were the “first couple” of wrestling, and their relationship flourished for the WWF promotion in the 1980s as well as the WCW promotion in the 1990s. Miss Elizabeth was present at ringside almost entirely for the psychological morale of Savage, Hogan or other wrestlers she was supporting. However, she had a knack for distracting referees, and the refs were all too eager to have extended chats with her when she climbed up onto the apron during a match. For the Monday Nitro years and the rise of the nWo bully faction, Miss Elizabeth became more ruthless and cunning, but she never turned heel in the mind of the fans. The strength of Miss Elizabeth's character was that her silence and mystery promoted a sense of privacy and independence which allowed her to serve as a symbol for male viewers. Boys and young men could project their imagination's ideal of femininity onto Elizabeth and this allowed them to reflect on their own urges toward aggression, brutality as well as their motivation for a desire in physical violence. Miss Elizabeth’s character was a powerful promotion of emotional and aggressive balance for male viewers, while her representation of the feminine had a therapeutic quality for young male viewers which is sorely lacking in the contemporary landscape of professional wrestling.

Professional wrestling has always been an alternative to real brutality and violence – its vaudeville origins were rooted in Christian ideals which had demanded through the social status quo an alternative entertainment form to that of real pugilism and boxing events. We watch wrestling for a cathartic release of the suppression of our individual and collective guilt for desiring real violence. That process of catharsis requires conscientious moments of self-reflection in order to maintain a balanced psyche, and the valet was a valuable tool toward that goal. Professional wrestling may always be perceived as a “lowbrow” entertainment form, however, it was briefly developing a sophisticated character as a medium until the laissez-faire capitalist monopoly of the industry circumvented further progress in that regard.

The valet is a critical companion for the professional wrestler. She will often be seen at ringside cheering for her partner, but she can also serve as an effective distraction for the opponent and often for the referee. The valet is available for assistance during a match whereby she can pass illegal objects to her partner in the ring which often shifts the match back in their favour. Typically, the valet is demure, whereby she is seen but not heard. The valet is totally distinct from the diva (female wrestler) because the former will only become a combatant while under extreme duress. As such, the valet has been unduly criticized for being a damsel-in-distress stereotype.

WCW had an illustrious array of valets, especially during the Monday Nitro years. After 1999, professional wrestling put an undue emphasis on diva wrestlers, resulting in women in the industry being known more for their brutality than for their grace. I would conjecture that this has not been a positive complement to the male wrestlers and that it has chased away many of the dilettante viewers who in the 1980s and 90s had constituted the medium as having mass appeal. The feminine wiles of the valet once trumped the female savagery of the diva in professional wrestling, and this was a critical component for the cathartic release for male viewers. The valet representing the feminine became a psychological device for self-reflection for the male viewer whereby that male might use the valet’s character and representation to reflect on their own motivations for desiring base simulated violence and brutality.

The exemplar valet was Miss Elizabeth, and for professional wrestling she was magic. Her demure and coy personality was a perfect complement for the wild, madness of her long-time partner and real-life husband, “Macho Man” Randy Savage. Truly, they were the “first couple” of wrestling, and their relationship flourished for the WWF promotion in the 1980s as well as the WCW promotion in the 1990s. Miss Elizabeth was present at ringside almost entirely for the psychological morale of Savage, Hogan or other wrestlers she was supporting. However, she had a knack for distracting referees, and the refs were all too eager to have extended chats with her when she climbed up onto the apron during a match. For the Monday Nitro years and the rise of the nWo bully faction, Miss Elizabeth became more ruthless and cunning, but she never turned heel in the mind of the fans. The strength of Miss Elizabeth's character was that her silence and mystery promoted a sense of privacy and independence which allowed her to serve as a symbol for male viewers. Boys and young men could project their imagination's ideal of femininity onto Elizabeth and this allowed them to reflect on their own urges toward aggression, brutality as well as their motivation for a desire in physical violence. Miss Elizabeth’s character was a powerful promotion of emotional and aggressive balance for male viewers, while her representation of the feminine had a therapeutic quality for young male viewers which is sorely lacking in the contemporary landscape of professional wrestling.

Professional wrestling has always been an alternative to real brutality and violence – its vaudeville origins were rooted in Christian ideals which had demanded through the social status quo an alternative entertainment form to that of real pugilism and boxing events. We watch wrestling for a cathartic release of the suppression of our individual and collective guilt for desiring real violence. That process of catharsis requires conscientious moments of self-reflection in order to maintain a balanced psyche, and the valet was a valuable tool toward that goal. Professional wrestling may always be perceived as a “lowbrow” entertainment form, however, it was briefly developing a sophisticated character as a medium until the laissez-faire capitalist monopoly of the industry circumvented further progress in that regard.